In this paper, Chatham House Director Robin Niblett sets out a proposed blueprint for Britain’s future foreign policy. Rather than reincarnate itself as a miniature great power, he argues that the country has the chance to remain internationally influential if it serves as the broker of solutions to global challenges.

The paper lays out six international goals for the UK that offer the best points of connection between its interests, resources and credibility. These are: protecting liberal democracy; promoting international peace and security; tackling climate change; enabling greater global health resilience; championing global tax transparency and equitable economic growth; and defending cyberspace.

In pursuit of these goals, the UK will need to invest in and leverage its unique combination of diplomatic reach, diverse security capabilities and prominence in international development. It should use these assets to link together liberal democracies and, where possible, engage alongside them with other countries that are willing to address shared international challenges constructively.

Summary

- Britain has left the EU and now the safe harbour of the EU’s single market and customs union at a time of heightened global risk. The COVID-19 pandemic has stalled globalization and intensified geopolitical competition.

- For its supporters, part of the logic of Brexit was that a more sovereign ‘Global Britain’ could pursue its commercial interests more successfully and enhance its voice internationally. Today, however, the UK must contend with greater protectionism, a more introspective US, no ‘golden era’ in relations with China, and gridlock in most international institutions.

- The incoming administration of Joe Biden will seek to heal America’s relations with allies in Europe and Asia. But Brexit Britain will have to fight its way to the table on many of the most important transatlantic issues, with the EU now the US’s main counterpart in areas such as China relations and digital taxation.

- Nevertheless, the UK embarks on its solo journey with important assets. It will still be the sixth- or seventh-largest economy in the world in 2030, at the heart of global finance, and among the best-resourced behind the US, China and India in terms of combined defence, intelligence, diplomatic and development capabilities. Even outside the EU, its government will be better networked institutionally than almost any other country’s. And the soft power inherent in its language, universities, media and civil society can enhance the influence of British ideas.

- But assets do not automatically equate with influence. There needs to be a vision for Britain’s international role, and the political will, resources and popular support to put this vision into action.

- A central question, then, is to what end should the UK combine its resources and enhanced autonomy on the international stage? Rather than try to reincarnate itself as a miniature great power, the UK needs to marshal its resources to be the broker of solutions to global challenges. And it should prioritize areas where it brings the credibility as well as the resources to do so.

- Six objectives meet these criteria. They are protecting liberal democracy; promoting international peace and security; tackling climate change; enabling greater global health resilience; championing global tax transparency and equitable economic growth; and defending cyberspace.

- Which countries should Britain engage in order to pursue these objectives? Shared geography and policy approaches mean the EU and its member states will be the most closely aligned with Britain across all six objectives, despite Brexit. The US comes next, given its unparalleled resources and special security relationship with the UK.

- The large, economically significant Asia-Pacific democracies that are already part of British and US alliance structures – such as Australia, Japan and South Korea – should also be a priority, given the increasing pressure they face from a stronger and more assertive China. So should sub-Saharan Africa, given the many challenges facing its rapidly growing populations and its proximity to the UK.

- In contrast, some of the original targets of ‘Global Britain’ – China, India, Saudi Arabia and Turkey – may be important to the UK’s commercial interests, but they will be rivals or, at best, awkward counterparts on many of its global goals.

- Three areas are ripe for Britain to tackle as a global broker in 2021, given the imminent arrival of the Biden administration. First, the UK can leverage its world-leading commitments to carbon emissions reduction alongside its co-chairmanship of COP26 to secure stronger national commitments on climate change from the US and China, the world’s two largest emitters.

- Second, the UK can leverage its strong position in NATO alongside a more transatlanticist Biden administration to broker closer working relations between NATO and the EU, especially on cybersecurity and protecting space assets, critical new priorities for the safety of European democracies.

- Third, the UK can use its presidency of the G7 in 2021 to start making this anachronistic grouping more inclusive. Rather than enlarging it to a catchy but arbitrary ‘D10’ or ‘Democratic Ten’, Britain could reach out to other mid-sized G20 democracies such as Australia, Indonesia, Mexico, South Africa and South Korea as and when they are willing to commit to joint action towards shared objectives.

- It could also link up its G7 programme with the Summit for Democracy, which Joe Biden has committed to host in 2021 to tackle the serious challenges now facing democracies at home. Britain could help define this agenda by convening meetings between officials, NGOs and US technology giants and brokering practical ideas to combat misinformation and disinformation.

- Outside the EU, the UK’s new international role will require additional resources. The government’s announced increase in defence spending is an important recognition of this fact. The proposed cut in development assistance to 0.5 per cent of gross national income is not. And the UK will be unable to play a meaningful global role unless it spends significantly more on its diplomatic resources.

- A positive reputation for Britain as a valued and creative broker in the search for solutions to shared problems will need to be earned. It will emerge only from the competence and impact of Britain’s diplomacy, from trust in its word, and from a return to the power of understatement for which the country was so widely respected in the past. Britain’s G7 presidency and co-chairmanship of COP26 in 2021 will be critical first tests.

01 Introduction

Outside the EU, Britain’s international policies will still require trade-offs between the desire for political autonomy and the realities of global interdependence.

On 31 December 2020, Britain left the limbo of its transitional status within the EU’s single market and customs union and began to exist again as an autonomous state – or as autonomous as it is possible to be in today’s world as a medium-sized, relatively wealthy and well-resourced country. What are the principal international risks to the UK’s prosperity and security over the coming years, and what opportunities could the country pursue in its new guise? What are its relative strengths and weaknesses in the global and regional contexts? What international goals should current and future governments realistically set? And how can they make a positive contribution on the global stage, given limited resources? This paper seeks to answer these questions.

It starts by noting that the speed of global change in the past 10 years has been disorientating:1 a disruptive US administration has called into question the international institutional structures that the UK had helped to build; China has emerged as the world’s second-most-powerful state – resolutely authoritarian but enmeshed in the global economy; the legacy of failed foreign incursions and weak governance led to the rise of Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which then fell almost as quickly, leaving much of the Middle East and North Africa region at its most unstable in generations; African states teeter between dynamic growth and collapse; the COVID-19 pandemic has stalled what was a hyperglobalizing world economy and deepened inequality; and mass access to instant information and disinformation has driven political awakening and polarization across the world. We are also witnessing the beginning of the end of work as people knew it, as the technology revolution courses through all corners of economic life; and the first devastating impacts on humanity and biodiversity of decades of growing carbon emissions and global warming.

What a time for Britain to strike out on its own. For some, these profound changes are precisely the reason why the UK needed to leave the EU and regain greater sovereignty over its future, rather than remain tied to what they see as a slow-moving, undemocratic institution with rigid regulatory commitments. For others, these changes are precisely the reason why the UK needed to remain embedded in the EU, an institution whose economic size and clout gave the UK a stronger voice and greater protection than it could ever achieve on its own.

With Brexit now in the rear-view mirror, this paper puts forward a simple argument. The UK has the potential to be globally influential in this turbulent world. But only if its leaders and people set aside the idea of Britain as the plucky player that can pick and choose its own alternative future. Instead, they need to invest in the bilateral relationships and institutional partnerships that will help deliver a positive future for the country as well as for others.

Successfully reimagining the UK’s role will clearly require difficult choices and trade-offs. But if the current government and its successors can connect a positive sense of shared national purpose with the country’s still significant economic, diplomatic and security resources, then Britain could serve as an example for the many other countries which face similarly difficult choices between notions of national identity and the pressures of globalization, between demands for national political autonomy and the realities of global interdependence.2

On paper, the UK may have more sovereign power than before, including over its immigration, environmental, digital and trade policies. In practice, its continued interdependence with European and global markets will severely limit its sovereign options. The country will no more be able to protect itself from global challenges, whether pandemics, terrorism or climate change, than it could as a member of the EU. The UK will no longer be directly subject to EU decisions and laws. But it will be just as dependent on its European neighbours for its economic health and security in 2026, for example, as it was in 2016 or, for that matter, a decade earlier.

The UK has the potential to be globally influential in this turbulent world. But only if its leaders and people set aside the idea of Britain as the plucky player that can pick and choose its own alternative future.

Moreover, the idea that the UK can now pursue a more independent foreign policy ignores the country’s constrained circumstances at the start of the 21st century. In the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak, the national finances will take many years to recover, with knock-on effects for the UK’s capacity for international influence. This will only increase the need to work with others. The country also faces an image problem. The UK embarks on its journey at a moment when its competence is being called into question as a result of the government’s handling of the pandemic. Its ideas for ‘Global Britain’ were already a tough sell when so many of its partners did not understand the logic of Brexit in the first place. The government’s use of the term ‘Global Britain’ implies that leaving the EU has freed Britain to become more internationally engaged than before. And yet, Brexit was an act of disengagement with its closest neighbours. And there is another point of ambiguity. The notion of ‘Global Britain’ may have a convenient alliteration with ‘Great Britain’, but in the minds of many, Britain became ‘Great’ by building a world-spanning empire whose injustices and inequities are now rightly being re-examined. The government will need to be judicious in how it now goes about communicating its global agenda, especially among its Commonwealth partners.3

The idea that the UK can now pursue a more independent foreign policy ignores the country’s constrained circumstances at the start of the 21st century. This will only increase the need to work with others.

After assessing the international context (Chapter 2), this paper considers the domestic and comparative contexts in which the government must develop and execute its foreign policy, underlining the considerable strengths that the UK will possess but identifying challenges and points of weakness (Chapter 3). The paper then lays out six broad international goals for the UK that offer the best points of connection between its interests, resources and credibility (Chapter 4).

Recognizing that progress in all areas will rely on cooperation and coalition-building, the paper identifies which will be the UK’s most important bilateral relationships, while pointing out the challenges each relationship poses (Chapter 5). The paper also highlights that the UK will need to ensure it is a valued member of institutions that will help it achieve its goals, but that this will require more flexibility and creativity than in the past (Chapter 6). It then underlines the increase in spending that an effective post-Brexit role implies, especially in diplomacy (Chapter 7). The paper draws these points together in its conclusion (Chapter 8) and argues that the UK should invest in becoming a global broker, leveraging its unique assets to link together liberal democracies at a time of strategic insecurity and engage alongside them with other countries that are willing to address shared international challenges constructively.

While the paper explores the roots of current popular ambivalence towards British foreign policy, it does not take up the likelihood or potential impacts of a break-up of the UK on Britain’s future global influence. This would undoubtedly be a serious development, reputationally and materially. But it would not undercut Britain’s core capabilities for brokering consensus among like-minded countries, and between them and other stakeholders, which would remain a worthy ambition for the UK’s future international role.

02 A splintered world

The UK could hardly have chosen a more difficult moment to reinvent itself as a global actor. Its most important bilateral and institutional relationships are in flux.

Britain’s circles of influence

Since 1945, British governments have had to manage what can be described as four ‘circles’ of international interest and leverage. These encapsulate continental Europe; the US; a small group of strategically important countries with whom the quality of bilateral relations has had an outsized effect on UK prosperity and security, including China, Japan, Russia and Saudi Arabia; and the rest of the world, with the Commonwealth providing some additional connectivity to an otherwise heterogeneous set of relationships.4

Recasting the UK’s relations with any one of these countries or groups has proved very difficult in the past, and has carried unintended consequences. Trying to retain the British empire after the Second World War turned out to be a lost cause, even as it led Winston Churchill to dismiss the alternative of the UK being a founding member of a more united Europe. Recasting the ‘special relationship’ with the US after the debacle of the Suez crisis was a major success for the Harold Macmillan government in the 1960s, but it cost him Britain’s first shot at joining the then European Economic Community. Trying to strike the right mix of engagement with and detachment from the process of European integration proved politically corrosive for the governments of Margaret Thatcher and John Major. Tony Blair’s efforts to find a third way for relations with the EU foundered on his commitment to the US and George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq. Having entered government committed to ‘stop banging on about Europe’, David Cameron tried to reconnect the UK with the world’s rising powers (a forerunner of Boris Johnson’s idea of a ‘Global Britain’) and opened what some anticipated would be a ‘golden era’ in relations with China. This plan failed, after Cameron chose to renegotiate Britain’s relationship with the EU and the ensuing referendum consumed his premiership.

Today, Britain faces a truly daunting task. In the coming years, its government will have to reset its relations with countries not within one or two of these circles, but across each circle simultaneously. And, if this were not enough, the international context into which a newly independent ‘Global Britain’ was meant to slot so easily no longer corresponds, if it ever did, to its proponents’ vision. Each of Britain’s four circles of influence is in flux.

Stuck with Europe

In some ways, the relationship with the EU may prove the most straightforward to reset. Despite the acrimony that surrounded Britain’s withdrawal from the EU and departure from its single market and customs union, geographic proximity and deep economic interconnections will force the UK government and its European counterparts towards constant compromise around their future co-existence. The net result, however, is that the UK will end up spending more time managing its relationship with EU institutions and member states than it did when it was an EU member, not least because the EU will continue to evolve.

The prospects of EU collapse are remote. Instead, in the wake of the 2008–10 global financial crisis, Brexit, the emergence of a more confrontational US and now the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a palpable desire within the EU for it to have greater strategic as well as economic autonomy. This goal should be easier to achieve with the UK no longer at the table constantly seeking to limit the EU’s accretion of institutional power.

In some ways, the relationship with the EU may prove the most straightforward to reset.

Nevertheless, this desire will struggle against the inward focus of the EU’s main business, and the tensions this reveals between the Union’s intergovernmental and supranational identities. Each step towards deeper integration – the latest being its €750 billion pandemic recovery fund – evokes a counter-reaction within and between member states. The deepening divergence in economic fortunes that COVID-19 is causing between member states will exacerbate underlying tensions, especially between economically harder-hit countries in the EU’s southwest and better-prepared ones in the northeast. This tension between the search for greater European strategic autonomy and its internal limits will leave space for constructive engagement between the UK and the EU on issues of global governance and foreign policy.

Most EU members gain foreign policy influence by banding together under the EU banner, even if collective action is hard to develop and execute. But for the UK, the process of agreeing common foreign policy positions among 28 states with distinct histories, cultures, national interests and capabilities was not only time-consuming and distracting, but increasingly disempowering. As a non-member, the UK will no longer continually have to resist an extension of EU competence into aspects of its foreign and security policy. And the more uncertain the world is beyond Europe, the more the UK and its continental counterparts will try to band together. This tendency has been visible since the Brexit referendum, with the UK and the EU adopting common positions on Iran, the Middle East peace process and World Trade Organization (WTO) reform, as well as in preparations for the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in November 2021.

A diminished special relationship

EU–UK cooperation on foreign policy has been encouraged by the antagonistic and unpredictable foreign policies of the Trump administration. The outcome of the US presidential election on 3 November 2020 will have a profound effect on the style, content and impact of US foreign policymaking. When Joe Biden enters the White House at the end of January 2021, he will bring with him an experienced team of foreign policy professionals who understand the value of international alliances. They will seek to repair frayed relations with traditional allies, although they will also expect an acceptance of America’s return to a global leadership role.

While the forthcoming presidential transition is of great consequence globally, the essence of the US–UK relationship is unlikely to change much. The US will remain Britain’s most important ally in the true sense of the term: the country on which the UK depends existentially for its security, and with which it has the closest and most extensive bilateral security relationship, stretching from nuclear to intelligence cooperation. In return, the UK will remain a natural partner in US alliance-building and coalition action. Securing British military assistance for US policies and deployments in the Gulf, Afghanistan or the South China Sea, for example, will remain important to US policymakers, even if UK contributions are relatively small in material terms.

But Biden and his administration will know that the UK has lost one of its most important assets as an ally, which was to bring its influential voice to bear in EU decision-making. And EU decisions will be of ever greater importance to the US – whether on sanctions towards Iran and Russia, or on the regulation and taxation of US technology giants. Future US administrations will therefore target a greater share of their diplomatic effort towards the EU and key EU bilateral relationships, principally with Paris and Berlin. The UK will constantly need to fight its way to the table in these transatlantic negotiations, now that it has lost its automatic seat as an EU member. If the US cannot come to agreement on a particular matter with the EU, then securing UK buy-in on a US policy position, potentially as a counterweight to the EU, will be a next best option for decision-makers in Washington, as was the case over the Trump administration’s efforts to eject the Chinese technology firm Huawei from constructing 5G telecommunications networks in Europe.

Regardless, as a non-EU member, the UK will come under greater bilateral pressure than before to demonstrate its loyalty to the US, or risk paying a price as the junior partner in the relationship. The test for British governments will be whether they can turn the UK’s greater policy autonomy and nimbleness as a non-EU member into an asset in the relationship with the US.

End of a golden era?

The UK has left the EU and enters a new phase in its relations with the US at a time when the world beyond the North Atlantic community is in turmoil. One of the main drivers of this turmoil is the seemingly inexorable rise of China. China’s mix of growing economic influence and diplomatic assertiveness is not only a challenge to the UK individually; it will also be a central feature of Britain’s relations with the EU, the US and other diplomatic partners.

Under President Xi Jinping, the Communist Party of China (CPC) has reasserted authoritarian controls that it had eased in the reformist period during and after Deng Xiaoping’s leadership. President Xi’s recentralization of power and drive to create around himself a cult of personality reminiscent of the Mao era pose new domestic risks to China’s development, as fealty replaces initiative and experimentation among China’s public and private sector leaders. In this context, the detention of some 1 million Uighurs in re-education camps, their placement into forced labour programmes, the now-regular arrests of Chinese human rights lawyers and the roll-out of an Orwellian social credit system are narrowing the scope for China to maintain constructive relations with democratic states, including the UK.

China’s handling of the COVID-19 outbreak in early 2020 exposed the negative effects of the opaque and secretive culture of the CPC.5 Watching Beijing instrumentalize its medical support to afflicted countries for diplomatic gain was all the more galling for Western policymakers. But as US and European criticism of China’s role in the COVID-19 outbreak grew, party officials in Beijing saw the criticism as further evidence that the West would resist China’s return to being a regional and world power. ‘Wolf warrior’ diplomats outdid each other in challenging Western narratives about COVID-19, while Chinese intelligence agents appear to have amplified disinformation about US and other governments’ responses to the virus.6

Combined with the decision by the National People’s Congress, China’s legislature, in May 2020 to impose a draconian national security law on Hong Kong, the growing estrangement between a more authoritarian and globally assertive China and much of the rest of the world has exposed the overambition of the joint political rhetoric in 2015 about establishing a ‘golden era’ in relations between the UK and China. Instead, there has been an inevitable anti-China backlash in the UK, as there has been across all Western countries.7

The short-lived ‘golden era’ in Sino-British relations – to the extent that it ever existed – is therefore over. More to the point, as bipartisan US opposition to China’s growing global influence deepens, the US, the UK and other US allies may slip into a new form of economic Cold War, involving investment restrictions, targeted sanctions and a decoupling of their technological sectors, with Taiwan an ever-present potential flashpoint.

The UK is having to choose between the world’s two largest markets, rather than being free to engage fully with both as it had intended.

There will be little, if any, scope for Britain to demonstrate its new global ambitions by prioritizing its economic relationship with China. Instead, the UK is having to choose in effect between the world’s two largest markets, rather than being free to engage fully with both as it had intended. And, when forced to pick sides, its inescapable choice will be in favour of the US, given Britain’s dependence on the US for its security and the close political, economic and cultural ties between the two countries.

The new ideological divide

The differences with the US–Soviet Cold War, however, will also be notable. China does not enjoy the support of a military alliance equivalent to the Warsaw Pact or, indeed, any reliable group of allies to amplify the risks posed by its growing military reach. Nor does China appear to want to establish itself as an alternative pole to the West. On the other hand, most of America’s allies today lack a shared unity of purpose towards managing China’s rise, given the absence of a clear threat from China to their survival and the fact that they benefit from its economic growth. To the contrary, there is an overwhelming desire among most governments and peoples – whether China’s neighbours or its distant trading partners – to remain non-aligned in the face of this neo-Cold War and to resist becoming part of a securitization of the US stand-off with China.

But history is replete with examples of how fear and mistrust between an established great power and a new contender can overcome the best intentions on both sides, as Graham Allison and others have persuasively argued.8 And, despite frequent commentary to the contrary, there is a growing ideological dimension to the stand-off between China and the US. The world is witnessing the re-emergence of a struggle between, on the one hand, governments and societies that tend to prize the liberty of their citizens – supported by representative systems of governance and strong civil societies – and, on the other, governments that to a greater or lesser extent expect their citizens to subsume their individual liberty to social stability and the sovereignty of the state. Most of the latter group view the checks and balances that provide accountability in liberal democracies as an unacceptable challenge to state authority, and civil society as a threat.

Although their respective leaders have profoundly different backgrounds and motivations, China and Russia are standard-bearers of the authoritarian system. Russia goes as far as to engage in political warfare to undermine the cohesion of democracies that its leadership perceives as threatening its own future security, using the openness of democracies’ political systems against them.9 But China and Russia are not alone. The huge material benefits available to those who fight their way to the top to lead authoritarian countries mean that the spread of free and open societies so hoped for after 1989 has at best ground to a halt and, in many cases, is receding, even in Europe.

In the meantime, Russia under Vladimir Putin and China under Xi have sought to buffer their national systems by creating new groupings of states that either subscribe to similar political approaches or are happy to show solidarity. Turkey and India – two priorities for the UK’s post-Brexit economic diplomacy – are among the countries whose governments readily participate in or attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, a grouping of states led by Beijing and Moscow designed to resist the penetration of Western interests and values in Eurasia.

The emergence of this new divide in international affairs – between open societies where citizens have the capacity to fight for their rights and those where these rights are denied – was perhaps inevitable. The transformative learning moment of the end of the Second World War has receded into history, and the hope that accompanied the end of the Cold War has been diluted by the re-emergence of atavistic fears as the centre of global economic gravity has shifted from the West to the East. This divide will complicate the UK’s ability to deepen its diplomatic and commercial relations with many of the world’s most populous countries and fastest-growing economies.

Multilateralism at bay

Equally important has been the erosion of the idea among many Americans that the US should carry the principal burdens of leading international institutions ostensibly dedicated to spreading the values and rules of open societies. The election of Donald Trump in 2016 served as a wake-up call, inside the US and beyond, that many Americans had not benefited from post-1990 globalization, or from the institutions that promoted the neoliberal ‘Washington Consensus’. The 2020 US presidential election showed how many voters continue to appreciate an administration that focused on ‘America First’.

The US’s loss of confidence in the multilateral trading system has meant the return to a more protectionist, nation-first approach to international trade. Even post-Trump, it is hard to see Joe Biden or his immediate successors pivoting back to the mantra of free trade that the Johnson government in the UK so confidently asserts, especially after the costs of the COVID-19 pandemic compound the structural inequalities that have caused such deep divisions in American society.10 If the US remains unconvinced of the domestic benefits of the international trading system, few others will step up to take its leadership role. This means that the WTO, the institution on which the UK will now have to rely far more to uphold the rules governing international trade, may remain obstructed, even if the Biden administration lifts its predecessor’s block on new appointments to the WTO’s Appellate Body.

Furthermore, the COVID-19 crisis has exposed the risks of economic interdependence. Policymakers around the world are trying to shorten supply chains, bring more manufacturing onshore and place new checks on foreign investment. They are less supportive of the ‘just in time’ means of production and import and export processes that were the hallmark of the hyperglobalized pre-pandemic trading system. The retreat from the idea of ever more open global markets – on which the idea of a ‘Global Britain’ relies – will accelerate if the EU succeeds in establishing a border carbon adjustment mechanism as part of its commitment to the Paris Agreement climate goals. Such a mechanism would enable EU companies to compete on a level playing field with imports from countries that have lower or no restrictions on the carbon intensity of their manufactures. Depending on how the US, China and other countries with high-carbon-emitting industries respond, Britain may have to follow the EU lead on this new trade measure or be left to negotiate its way through a complex new thicket of global obstacles to international trade.

The danger is that the return to realist, ‘me first’ international relations and weak international institutions masks the historic scale and interconnected nature of the challenges facing all countries, including the UK.

Overall, international institutions which the US and UK jointly conceived in the 1940s, including the UN Security Council and the Bretton Woods agencies, have lost much of their influence. The credibility of the UN Human Rights Council has been undermined by the election of states associated with severe human rights abuses. Major international agencies are also having to compete with a smorgasbord of alternative institutions and arrangements, from the G20 to the BRICS summits to regional initiatives such as the newly agreed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). These more informal institutions are designed to facilitate political co-existence and economic gain between states on different political journeys. But they are not clubs of the like-minded, committed to enforcing or enlarging the rules of liberal democracy and transparent markets.

The danger is that this return to realist, ‘me first’ international relations and weak international institutions masks the historic scale and interconnected nature of the challenges facing all countries, including the UK. But it also offers an opportunity. Helping liberal democracies face up to these shared challenges while building consensus with others for common action would be a worthy goal for Britain after Brexit.

03 Britain’s relative position

The UK will remain one of the few countries able to bring a full spectrum of assets to bear on its international interests, including diplomatic reach, diverse security capabilities and prominence in international development.

A strong starting point

It would be easy to assume that Brexit Britain will be a notable loser from the splintering of international relations outlined in the previous chapter. The UK is a privileged founding member of the institutions that govern the rules-based international system now under threat. By leaving the EU, the country has nonetheless chosen this moment to unmoor itself from one of the world’s three main geo-economic actors and the protections that it offered. But, seen from a selfish perspective, the UK starts off in a better position than most other countries trying to navigate an environment of heightened geopolitical competition and semi-functional international institutions. The question is whether it can sustain its strong position on the world stage and avoid losing influence in comparison to other players.

The UK is a privileged founding member of the institutions that govern the rules-based international system now under threat.

The UK embarks on its solo journey with a seat in all the world’s major multilateral organizations, formal and informal, from the IMF to the G7 and G20. Through these it can try to defend and promote its interests. It will remain a permanent, veto-owning member of the UN Security Council, keeping it at the heart of major-power diplomacy. The UK’s place in these institutions is further cemented by the fact that it will remain one of the world’s few recognized nuclear weapon powers and is a close ally of the US. The UK can also draw on a globally present diplomatic service supported by world-leading intelligence services.11 China overtook the US in 2019 in having the largest number of overseas diplomatic posts, with 276 such posts compared to 273 for the US. Nevertheless, if one excludes consulates and consulates-general, the UK remains in equal fourth place alongside Germany and Japan in terms of its total number of full embassies or high commissions and permanent missions – each country has 161 such posts.12

This ranking amid a cluster of the world’s other mid-sized countries also applies to the UK’s defence spending, which, at $55 billion in 2019, puts the country sixth, just ahead of France, Japan and Germany.13 Among similar-sized powers, however, the UK is one of the few that possesses a full spectrum of rapidly deployable armed forces and cyber capabilities. This contrasts with the capabilities of two countries that spend more on defence in gross terms – India and Saudi Arabia – and also with the situations of Germany and Japan. Even after major defence cuts and force reductions since the end of the Cold War, the UK is capable of contributing to coalition operations around the world and remains one of the most influential members of NATO.

To these elements of military power can be added the UK’s network of military bases and garrisons, which are strategically located across the world, from Ascension Island in the Atlantic to Belize near the Caribbean, Cyprus in the eastern Mediterranean, Bahrain in the Gulf, Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean and Brunei in the South China Sea. Only the US has a larger network.14 Bolstering the political-military influence from its military expenditure, bases and intelligence capabilities is its status as one of the world’s leading arms exporters. Notwithstanding domestic legal challenges to its exports to Saudi Arabia, the UK was the second-largest arms exporter in the world in 2018 and 2019.15

Finally, the UK has been the world’s third-largest purveyor of official development assistance (ODA) – $20 billion in 2019. The UK spent two-thirds of this amount bilaterally, and contributed one-third to the World Bank and the EU.16 Country directors from the former Department for International Development (DFID) are important players in countries across the world, where UK spending generally dwarfs that of others. The 2020 merger of DFID into the newly created Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) is designed to create greater synergies between the UK’s development spending and its diplomatic priorities. Although there are concerns about the impact of the merger on the interests of the world’s poorest, this combination of assets gives the UK the rare capability to blend hard influence, such as military training missions and naval port visits, with its softer foreign assistance.17

So while its relative position on some measures of global power, such as share of world GDP or size of its military, has been slipping for decades, Britain has remained influential because it is one of the few countries capable of combining its diverse national assets – diplomatic, military, intelligence and humanitarian – to pursue its interests beyond its shores. As Robert Zoellick, a former US cabinet member, commented recently, ‘full-service powers get extra points’ – meaning that the capacity to blend different forms of political power and persuasion enhances a country’s potential influence, and hence the benefits that can accrue to national prosperity and security.18

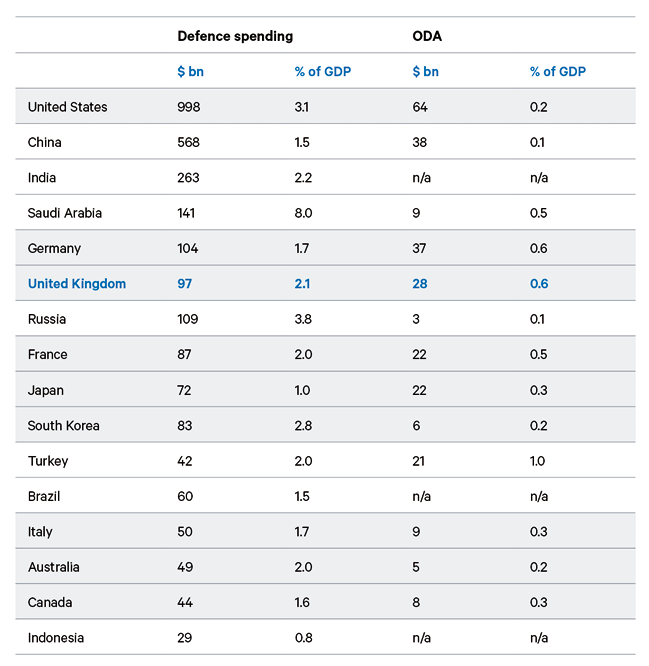

Taking all these elements together means that the UK currently sits in the second tier of the world’s 10 best-resourced countries in international affairs, well behind the US and China, but alongside France, Germany, India, Japan, Russia and Saudi Arabia (see Table 1 below).

Table 1. Top countries by defence / ODA spending and diplomatic reach

Defence spending, 2019

ODA, 2019

Diplomatic posts

$ bn

% of GDP

$ bn

% of GDP

Embassies, high commissions and permanent missions

United States

685

3.2

34

0.16

177

China

181

1.2

n/a

n/a

177

Saudi Arabia

78

9.9

5

0.57

98

United Kingdom

55

2.0

20

0.70

161

Germany

49

1.3

25

0.64

161

France

52

1.9

13

0.47

176

Japan

49

1.0

15

0.30

161

Russia

62

3.6

1

0.07

155

India

61

2.1

n/a

n/a

128

South Korea

40

2.4

3

0.16

119

Italy

27

1.4

5

0.26

132

Australia

25

1.8

3

0.22

85

Brazil

27

1.5

n/a

n/a

150

Notes: Countries listed in descending order of total spending (i.e. defence + ODA). n/a = ‘not available’. Sources: International Institute for Strategic Studies (2020), The Military Balance 2020; OECD (2020), ‘Net ODA’, https://data.oecd.org/oda/net-oda.htm (accessed 23 Oct. 2020); and Lowy Institute (2020), ‘Lowy Institute Global Diplomacy Index’.

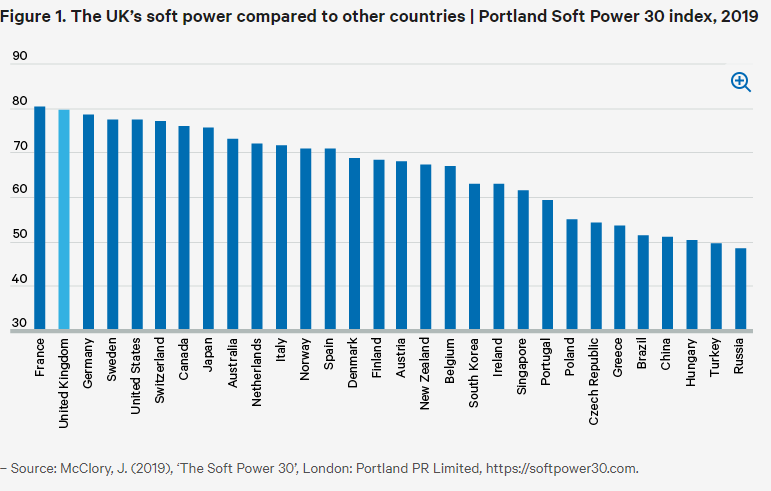

For all the criticism the UK government has received as a result of its messy withdrawal from the EU, and its mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic, Britain also retains considerable reserves of soft power: the ability to engage internationally and influence global outcomes irrespective of the government’s diplomatic efforts at persuasion or coercion.

Deeply embedded expertise in the legal drafting of diplomatic texts and agreements, along with native command of the world’s effective lingua franca, gives British voices outsized influence in international debates and negotiations.

Deeply embedded expertise in the legal drafting of diplomatic texts and agreements, along with native command of the world’s effective lingua franca, gives British voices outsized influence in international debates and negotiations.19 International law draws heavily not just on British legal traditions but also on highly trained British lawyers and judges, often recognized as leading experts in their field. The BBC, the Economist, the Financial Times and the Guardian also leverage the power of the English language along with their independent editorial lines to dominate reporting and commentary on international affairs. London’s position as one of the world’s leading financial centres puts it at the heart of new developments in financial technology, products and regulation, and often ensures the UK a prominent role managing investments into infrastructure projects in emerging markets.

The education sector is another asset. Though Brexit and COVID-19 have set back the continued expansion of UK universities, the high quality and scope of their research put Britain at the forefront of scientific breakthroughs, helping to attract foreign investment and human talent. Finally, the plethora of international NGOs clustered in the UK leverage Britain’s position as one of the world’s highest ODA spenders. This engages the UK in bottom-up responses to the challenges of resilience and growth in Africa and South Asia, regions with the world’s fastest-growing populations. In 2007 the then foreign secretary, David Miliband, described Britain’s role as one of a global ‘hub’.20

This role is supported by the country’s geographic location, and by its convenient position in a time zone between the Asian and American continents, which will be as valuable in the new era of Zoom meetings as it has been in the era of the telephone, email and air travel. This nexus of media, specialist publications, NGOs, policy institutes and academic centres gives British ideas a strong and substantive voice in international debates, from environmental protection to global health governance.

The government’s use of the term ‘Global Britain’ serves to remind others of these assets; it is also a rallying cry to UK citizens to be globally ambitious, and a commitment to its international partners that leaving the EU does not mean the UK will close in on itself. To the contrary, the Johnson government says it plans to go from being overly focused on relations with Europe to opening itself to the opportunities offered by the world as a whole.21 Whether those opportunities turn out to be harder to access or not is beside the point; the label ‘Global Britain’ implies that the country will ‘step up’, as Secretary of Defence Ben Wallace has put it.22

But enjoying unique reserves of soft power, a seat at most of the world’s top tables, and the assets to leverage the UK’s voice and support its interests does not guarantee an ability to lead global change or secure outcomes to the national advantage. This is especially true when the UK is detached from the main institutional actor in its region, the EU; when Britain’s most important ally, the US, is grappling to determine its own role in a new geopolitical contest; when alternative partners are dispersed around the world, each with their own domestic and regional concerns; and when the open, rules-based international system which the UK has long championed is under threat.

Before considering how the UK could adapt its international role to these changed circumstances, it is important to assess the resilience of its current national advantages, rather than taking them as a given in the future. How strong and sustainable will Britain’s hard power be as disruption from the COVID-19 pandemic consumes its economic resources and the political bandwidth of its leaders? How durable is its soft power? And how might societal and national divisions across the UK, sharpened by COVID-19, limit the government’s freedom of action?

The economic challenge

The standard line from the government is that, starting out as the world’s sixth-largest economy,23 the UK has a strong base from which to pursue its national and international ambitions; in other words, it does not have to rely on EU membership to amplify its economic potential. How does the evidence stack up?

The COVID-19 crisis makes any prediction about the global economy in 2030 highly speculative. The same goes for an individual country such as the UK, which was already struggling with weak productivity growth going into the pandemic and faced the prospect of post-Brexit disruption.24 Pre-COVID-19 assessments nonetheless projected that the UK would remain one of the world’s top 10 economies for at least the next decade, even though the US and China will swap positions at the top of the leader board and India will become the third-largest economy.

Table 2. The world’s largest economies, 2019 and 2030 | Nominal GDP in US$ at market exchange rates

2019

2030

1

United States

China

2

China

United States

3

Japan

India

4

Germany

Japan

5

India

Germany

6

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

7

France

France

8

Italy

Brazil

9

Brazil

Indonesia

10

Canada

South Korea

Sources: IMF (2020), World Economic Outlook Database, October 2020, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPD@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD (accessed 29 Oct. 2020); and OECD (2018), ‘Economic Outlook No 103 – July 2018 – Long-term baseline projections’, July 2018, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=EO103_LTB (accessed 29 Oct. 2020).

It now appears that most states will see their near-term growth prospects undermined by COVID-19, although China and its Asian neighbours are recovering the most quickly. The UK will be particularly hard hit in the short term because of its reliance on services to generate growth, tax revenue and employment. According to the Office for National Statistics, the UK economy was still almost 10 per cent smaller in the third quarter of 2020 than at the end of 2019, one of the worst performances in the world.25 The aviation, retail, hospitality and cultural sectors, in particular, may take a long time to recover as household consumption has suffered more in the UK than in many other markets.26 However, some parts of the UK economy, including professional services, have weathered the crisis relatively well. And the UK is less reliant than some major economies on manufacturing exports, which will be hard hit in the short term as negative or slower GDP growth cramps consumption outside the Asia-Pacific, and as many countries try to shorten supply chains to strengthen economic resilience.

The UK will no longer offer the same advantages as a cost-efficient gateway for non-UK manufacturing companies seeking to access the EU market.

Over the medium term, the UK faces a complex mix of risks and opportunities. On the plus side, unlike many developed nations, the UK has a relatively young population that continues to grow, which should help to stimulate economic activity. Helped by the Bank of England’s reputation for sound monetary stewardship, the government enjoys very low borrowing costs, with 10-year sovereign bonds currently being financed at rates in the region of 0.2 to 0.3 per cent. This gives the authorities plenty of room to back the economy through the COVID-19 crisis, even as the ratio of public debt to GDP passes 100 per cent.

On the negative side, growth will inevitably be hit by the UK’s exit from the EU single market, with the Office for Budget Responsibility projecting a 4 per cent loss of long-run output over the coming years, over and above the impacts of COVID-19.27 Even with the recently concluded UK–EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), UK goods exports to the EU will face customs and regulatory checks, and new minimum requirements for the amount of UK and EU content if they are to enjoy tariff-free access. In the near term, at least, UK services will also lose barrier-free access to EU markets, and UK-based companies will be unable to work with EU clients as effectively as they did when in the EU. Commercial services – including finance, education, professional services (accountancy, law, public relations), design and fashion – are the UK’s most successful export segment, and the EU has accounted for 40 per cent of UK service exports, generating a bilateral trade surplus in the UK’s favour, in contrast to UK trade in goods.

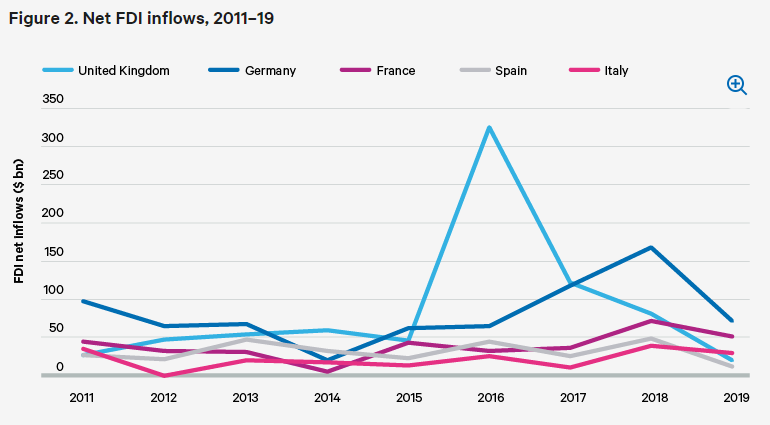

As a result, the UK may see further erosion of its coveted position among the top destinations for foreign direct investment (FDI) in Europe. The UK will no longer offer the same advantages as a cost-efficient gateway for non-UK manufacturing companies seeking to access the EU market. The challenge will thus be twofold. One will be to attract investors interested in tapping into Britain’s relatively large, young and wealthy domestic market. The other will be to continue to lure investors with the UK’s reputation and capacity for scientific innovation, and with its continued relative openness to human talent. The government appears committed to both objectives. But, even with continued UK participation in large EU research programmes under the new TCA, there will be new financial disincentives for students and researchers from continental Europe to come to the UK, which could undermine the UK’s leading position in university rankings and scientific research.28

In the meantime, the UK will need to keep a close eye on the health of its current account, which has been running a deficit of around 3–5 per cent of GDP since 2012.29 The challenge has been compounded by the post-referendum drop in the pound, which has contributed to the value of the UK’s overseas assets falling below the value of its external liabilities.30 And British citizens still show scant interest in becoming bigger savers: domestic savings rates have declined further relative to the UK’s main European peers since 2016.31 Establishing new free-trade agreements (FTAs) with partners such as the US or Mexico – or upgrading some of the FTAs the UK previously enjoyed as an EU member, as the government has recently done with Japan – will help, especially if the deals can be tailored towards UK strengths such as data services. But this will not compensate in the near or medium term for the loss of preferential access to the large, wealthy and nearby EU market.

Slipping, but still in the top tier

What might this all mean for Britain’s capacity for international influence? Given the COVID-19-straitened financial circumstances likely for the next three to five years at least and the opportunity costs of adjusting its economy to life outside the EU, the UK will have next to no additional resources to deploy to protect its interests and project influence internationally, as it repairs the fiscal damage caused by the pandemic (and by the state’s necessary response to it). But if the UK can at least sustain existing levels of international public spending as a proportion of GDP, then, given that other countries will be facing similar pressures, it should have sufficient resources to be able to remain a globally influential mid-sized power.

The UK will remain at the top of a cluster of countries in the second tier, with the combined material resources potentially to play a globally influential role alongside the same allies and partners as today.

To illustrate this point, the tables below use 2018 OECD projections of economic growth to 2030 to show how relative changes in GDP could affect trends in defence and development spending. These projections do not take into account the impact of COVID-19. But even if one country is hit more or less hard than others in the short term, the long-run impact over the next 10 years is likely to be limited enough not to change the projected rankings significantly.

Under this scenario, it looks likely that the UK will remain among the top 10 countries globally, not only in terms of total GDP, but also one of the wealthiest per capita among this group (see Table 3). Future British governments will therefore have the option to continue dedicating a meaningful proportion of GDP to their international priorities.

Table 3. GDP and population in 2030

Nominal GDP at market exchange rates

Population

$ bn

$ per capita

Million

% working age

China

37,890

26,585

1,425

67.4

United States

32,182

92,406

348

62.3

India

11,970

7,961

1,504

68.4

Japan

7,200

60,366

119

58.0

Germany

6,122

74,426

82

59.5

United Kingdom

4,599

66,143

70

61.9

France

4,368

63,722

69

59.7

Brazil

4,032

18,011

224

68.2

Indonesia

3,571

11,937

299

67.7

South Korea

2,963

57,571

51

64.8

Italy

2,948

50,320

59

60.9

Russia

2,869

20,245

142

63.0

Canada

2,752

67,253

41

62.2

Australia

2,455

86,853

28

62.4

Turkey

2,078

23,306

89

66.6

Saudi Arabia

1,759

44,744

39

72.8

Sources: OECD (2018), ‘Economic Outlook No 103 – July 2018 – Long-term baseline projections’; World Bank (2020), ‘Population estimates and projections’, DataBank, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/population-estimates-and-projections (accessed 29 Oct. 2020).

If we then take into account likely and announced spending plans alongside these projected growth trends in GDP (see Table 4 below), a second important takeaway is that the differential between the amount the UK spends in 2030 on its international priorities, alongside that of other mid-sized powers, and the larger amount China spends will have widened significantly. Still, if the UK can sustain current rates of both defence and development spending relative to GDP, a third important takeaway is that the UK will remain at the top of a cluster of countries in the second tier, with the combined material resources potentially to play a globally influential role alongside the same allies and partners (shaded in grey in Table 4) as today.

Table 4. Projected international spending in 2030

Notes: Countries listed in descending order based on author’s assessment of the future combined spending on defence and ODA as a percentage of projected GDP in 2030. Grey shading indicates UK and partner countries. n/a = not available. List excludes EU given its lack of control over defence spending. Sources: Author projections based on International Institute for Strategic Studies (2020), The Military Balance 2020; OECD (2018), ‘Economic Outlook No 103 – July 2018 – Long-term baseline projections’; and OECD (2020), ‘Net ODA’. National wealth and international influence can interconnect, but they do not necessarily correlate. Russia’s GDP is currently broadly equal to that of Canada, yet Russia is a far more influential country. For its part, the EU struggles to bring its collective weight to bear on questions of security and traditional foreign policy, but has proven adept at leveraging its combined market power in the field of global regulatory standards and in striking major trade agreements.

These are reminders that while the size and scope of the UK’s national assets will matter, they are no guarantee of future international influence. An effective strategy for their deployment will be at least as important. The likely change in Britain’s relative economic position in 2030 brings into sharp relief the need for the UK to focus its efforts and to coordinate its assets with its main partners if it is to have a good chance of achieving its global goals in the future. But, as discussed in the next section, any strategy will also depend in part on the licence that policymakers believe they have from the public to apply the country’s precious resources to the pursuit of their foreign and security policy priorities.

An ambivalent public

A country’s international influence depends on more than just its material resources. It also depends on a mix of intangibles, including technological innovation, the quality of policymaking, bureaucratic efficiency, and the competence and charisma of political leaders. Britain’s ability to build a world-spanning empire in the 19th century illustrates the relevance of this mix. Most of these dynamics lie beyond the remit of this paper. But one issue that must be considered is the level of popular cohesion in the face of future external challenges.

To start with, for all the new hurdles facing the UK after its exit from the EU, it is possible that there will be a new sense of national agency among British politicians and citizens. Outside the EU, UK policymakers will not be able to blame the EU for the country’s ills or hide the failures of policymaking in Westminster behind claims of an ‘undemocratic’ Brussels. By being more alone in the world, they will have a greater incentive to fix their own problems – and little choice but to do so. Perversely, membership of the EU appeared to disconnect many UK political leaders, on the right and left, from their predecessors’ traditional pragmatism. For over 30 years, the country indulged in an endless debate about the UK’s role in the future of EU integration, rather than making thoughtful assessments of how EU membership could help mitigate risks and maximize opportunities for the country.

Outside the EU, UK policymakers will not be able to blame the EU for the country’s ills or hide the failures of policymaking in Westminster behind claims of an ‘undemocratic’ Brussels.

Attitudes to European defence are an example of new-found British pragmatism. Despite continued misgivings after the Brexit referendum, Conservative policymakers have since stood aside to allow EU members to increase their defence integration.32 They no longer fear that each EU decision on foreign and security policy might be a precursor to an expansion of qualified majority voting that would circumscribe British sovereignty. But the potential for greater pragmatism in dealing with European neighbours on shared challenges falls a long way short of the ambitious foreign policy implied by the ‘Global Britain’ mantra. And the latest opinion polling raises questions about whether there will be public support in the coming years for an activist approach.

Britain emerged from its Brexit chrysalis and entered the COVID-19 crisis as a still-divided country. The 2019 British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey reveals that only 7 per cent of respondents felt ‘very strongly’ attached to one of the country’s political parties, equalling the record low proportion in the 2018 survey. In contrast, 45 per cent classified themselves as either ‘very strong’ Remainers or ‘very strong’ Leavers, 5 percentage points more than in 2018. Another third thought of themselves as ‘fairly strong’ Remainers or Leavers.33 The country is still split into two halves, therefore, with Remainers far more pessimistic and Leavers far more optimistic about their economic futures and national identity after Brexit.34

What might these popular attitudes mean for this and future governments as they seek to redefine the UK’s global role? The BSA survey points to an interesting development. Remainers and Leavers may still be deeply split on the value of the UK’s relationship with the EU, but they broadly share similar views on how to manage certain aspects of relations with the outside world after Brexit. For example, 48 per cent of Remainers join the 82 per cent of Leavers who believe EU migrants should go through the same entry requirements as non-EU migrants.35 At the same time, Remainers and Leavers both overwhelmingly support retaining the EU’s strong safeguards on animal welfare, reflected in their shared opposition to the import of hormone-treated beef and chlorinated chicken – a worrying sign for proponents of a more deregulated, free-trading Britain. On genetically modified crop imports, the Leavers are even more sceptical than the Remainers.36

Remainers and Leavers also appear united in their lack of trust in politicians and the political system. Only 15 per cent of those surveyed said they trust British governments ‘just about always’ or ‘most of the time’, while 34 per cent said they ‘almost never’ trust British governments, the worst figure since 2009 and the financial crash.37 And Leavers still trust government the least. Between 2016 and 2019, the number of Leavers who say they ‘almost never trust’ the government increased by 8 percentage points to 40 per cent.38 The one area where Leave voters are more trusting of the government than Remainers, however, is foreign policy. According to a survey by the British Foreign Policy Group (BFPG) published in mid-2020, a little under two-thirds of Leavers trust the government to act in the national interest on foreign policy. Remainers offer a mirror image, with close to two-thirds not trusting the government to represent the national interest.39

On the separate issue of interest and engagement in politics, the BSA survey shows that this grew among the public significantly around the 2016 referendum and – while having slipped somewhat – remains historically elevated.40 This could be healthy for the future of UK democracy, but it also could have a constraining effect on this and future governments’ room for manoeuvre on foreign policy. David Cameron notoriously discovered to his cost how cautious MPs have become in the face of a more engaged but sceptical public in respect of foreign policy, when in August 2013 he lost a Commons vote on conducting airstrikes against Syrian government forces as punishment for their use of chemical weapons against civilians. The fact that increased popular interest in politics is accompanied by an increase in political polarization means the government may struggle to gain majority public support for a more activist foreign policy. And, although there appears to be strong support for the UK continuing to spend nearly 3 per cent of GDP on all its international activities, this offers little guidance as to what majorities of the public believe this spending should be targeted towards.41

The fact that increased popular interest in politics is accompanied by an increase in political polarization means the government may struggle to gain majority public support for a more activist foreign policy.

To the extent that there is a popular mood around Britain’s place in the world, it is one of caution. The BFPG survey shows a sharp increase in the number of Britons who reject the notion of being a ‘global citizen’, up from 34 per cent of respondents in 2019 to 46 per cent in 2020.42 The BFPG survey also reported that 36 per cent of Britons would prefer the government to focus on the country’s own economic and security interests. Only 16 per cent believe the country should emphasize its support for democracy and human rights, and 32 per cent favour striking a balance between the two.43

Although there is still support for the UK’s traditional role in providing humanitarian assistance, only small percentages of those surveyed were interested in seeing British funds go to achieving more structural goals, such as increasing women’s education or protecting women from violence.44 There was similar popular ambivalence in a survey on NATO by the Pew Research Center. Some 65 per cent of respondents said they had a favourable view of NATO, but only 55 per cent said they would support the UK using military force if a fellow member were attacked by Russia (though this percentage is higher than in most other NATO countries).45

A key question is how this contradictory popular outlook will be affected by the COVID-19 crisis. A survey by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) in August 2020 argues that Britons are healing their Brexit divisions under the pressures of the pandemic.46 The survey also shows cross-party support for an internationalist UK foreign policy, as the pandemic has reminded the public of the country’s dependence on its overseas partners.47 But this healing has come at the cost of trust in the Johnson government, whose handling of the crisis has badly dented its reputation, with Conservatives being particularly critical.

Importantly for the substance of UK foreign policy, the survey shows a marked worsening in public perceptions of the US and China, and an improvement in perceptions of Germany.48 While the US figures will most probably change following the election of Joe Biden, another survey shows that negative perceptions of China have spiked in the UK, from 55 per cent of respondents in 2019 to 74 per cent in the summer of 2020.49 For Johnson there is the additional consideration that over 30 per cent of Conservative voters blame China for the scale of the damage wrought by the pandemic, compared with single-digit percentages among supporters of other British political parties.50

The current and future governments will need to consider the perspective of the younger generation of Britons when developing and implementing foreign policy.

COVID-19 has not dented the public’s desire to see the government be proactive in tackling climate change. In the recent ECFR survey, 62 per cent of respondents want stronger action to combat climate change, seeing parallels in the scale and impact of global warming and the pandemic, while only 9 per cent do not.51 This is a reminder that this and future governments will need to consider the perspective of the younger generation of Britons when developing and implementing foreign policy. Acutely aware of the risks from climate change, and embracing the social activism of the #MeToo movement and the desire to tackle structural injustices implicit in the Black Lives Matter movement, this next generation is more likely to hold the government to account over its statements about pursuing a values-based foreign policy. Young people will expect the political establishment to uphold the same commitment to environmental stewardship, social justice and good governance that it demands from multinationals and business leaders. The government will struggle to promote these principles domestically and then try to run a foreign policy that contradicts them.

It is hard to predict how these public perceptions will influence government policy. The combination of a public still divided over the impacts of Brexit, a significant loss of trust in politicians and the political system, and widespread popular caution about a more deregulatory UK trade policy could serve as constraints. The government’s promise to ‘level up’ the country socio-economically also creates the expectation that more resources will be focused at home rather than on foreign policy ambitions. And this all sets to one side the very real risk that the UK might break up at some point in the next five to 10 years, as Scottish and Irish nationalism feed off continuing post-Brexit and post-pandemic political turbulence.

So, the government’s licence to invest in strategic international goals will need to be earned by a successful performance at home. But now that the UK has left the EU but has been reminded by COVID-19 of the realities of interdependence and the benefits of international cooperation, there could be public support for a non-partisan international agenda that is seen to improve the country’s future well-being and security. Policymakers will also need to take into account some of the forward-looking aspirations of the UK’s younger generations, rather than tapping into nostalgic visions of Britain’s role in the world.

04 Global goals

The government should focus its foreign policy on six priority areas where the combination of its resources and credibility will enable the UK to have most impact.

As Britain reaches out to the world on its own, the government’s international goals should prioritize issues that most reflect a combination of three factors: their importance to the country’s interests given the splintered international context; the UK’s ability to bring assets to bear to make a difference; and whether the government carries the domestic credibility, including popular licence, to act. What, then, should the UK’s main goals be? The following sections outline six priorities that meet these criteria.

Human rights and democracy

First, the UK should protect human rights and liberal democracy around the world, and help other countries undertake their own journeys to systems of democratic governance. This is not a utopian aspiration; it is a realist goal rooted in the national interest. The UK will not want the world dominated by a growing number of insecure autocracies that, in almost all cases, struggle to meet the needs of their people and pay little attention to shared global problems. It makes more sense for the UK to be an anchor for liberal democracies at a time when these are under threat in many countries. Their health and survival will ensure the UK continues to have allies and partners who support a rules-based approach to international relations, thereby lessening the risk of conflict and instability; whose systems of political checks and balances, in challenging leaders who pursue personal enrichment at the expense of the public interest, provide more likely partners in tackling shared global challenges; and whose politicians and businesses come under pressure from civil society to combat rather than condone corruption, thereby also allowing UK companies to compete more effectively.

The UK brings significant assets to the pursuit of this goal. As a permanent member of the UN Security Council, it has an important voice in supporting the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As a core member of the Commonwealth, it has a regular forum in which to promote norms of accountable governance. As the leading member of NATO after the US and as commander of NATO’s Joint Expeditionary Force with a sizeable forward deployment of forces in the ‘High North’, Britain plays an important role in protecting some of Europe’s most geographically exposed democracies.52 Hosting one of the world’s leading financial centres, it has the capacity to sanction – alone and alongside others – individuals or governments that seek to undermine democracy at home or abroad.

Hosting one of the world’s leading financial centres, the UK has the capacity to sanction – alone and alongside others – individuals or governments that seek to undermine democracy at home or abroad.

The UK government has stated that supporting liberal democracy and human rights is one of its central goals, along with promoting free trade and the international rule of law.53 It has taken a number of concrete steps in support of this goal in the past year and a half. In mid-2019, in conjunction with the Canadian government, the UK launched an initiative on global media freedom.54 And it has taken a more proactive stance since the UK’s departure from the EU on calling out human rights abuses. It introduced new so-called ‘Magnitsky provisions’ as part of its new post-EU Sanctions Act, targeting individuals involved in human rights abuses in Russia, Saudi Arabia, Myanmar and North Korea.55 In June 2020, it convinced other G7 members to issue a statement critical of China, following the Chinese government’s imposition of the draconian national security law on Hong Kong.56 It followed this by offering a pathway to citizenship for all Hong Kong British National Overseas passport-holders, plus the 2.2 million entitled to apply for one; suspending its extradition treaty with Hong Kong; and including the territory in the British arms embargo with mainland China.57 In September, the UK government also began sanctions proceedings, ahead of the then-gridlocked EU, against individuals in the government of Aliaksandr Lukashenka in Belarus, in response to the regime’s political suppression following disputed elections.58

Notwithstanding the indifference that at least a third of the public conveys about the government pursuing a values-free foreign policy, a principled approach to human rights would be aligned with the growing popular demand for greater domestic equity and justice. And the UK has the interests, resources and credibility to make support for liberal democracy one of its priorities for the future. The arrival of the Biden administration also creates an opportunity for the UK to support the US’s possible return to the UN Human Rights Council as part of a team of countries committed to upholding the council’s true principles.

Peace and security

The goal of upholding and supporting liberal democracy is connected to what should be a second principal foreign policy objective, which is for the UK to support the emergence and maintenance of peaceful and thriving societies around the world. Increased geopolitical competition, failures of governance and growing environmental stresses are undermining international peace and security, especially in the Middle East, Africa and South Asia. Yet an expansion in the number of societies living in peace and security would have direct benefits for Britain’s own security and prosperity. It would ease the pressures contributing to illegal migration flows; it would limit the appeal of diverse forms of violent extremism and the risks to the UK from international terrorism; it would reduce the risk that communicable diseases overwhelm weak health systems and spread to the UK; and it would expand the potential circle of Britain’s economic partners.

Given the institutional, security and environmental challenges facing their rapidly growing populations, as well as their relative proximity to the UK, countries in sub-Saharan Africa should continue to be Britain’s main priority in this context.

The steps needed to progress towards this objective are well known. They are encapsulated in the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 16 (‘peace, justice and strong institutions’), which the UK and all other states have signed up to.59 The UK is well placed to support other countries in working towards the SDGs. Britain’s large foreign assistance budget gives it a strong voice in the UN’s multilateral development agencies, even after the announcement of a supposedly temporary fall to 0.5 per cent of gross national income (GNI) in the government’s November 2020 Spending Review. The country’s world-leading humanitarian and development NGOs bring important experience, strong networks and their own funding to local projects.60 In addition, the government has recently pledged £515 million to help more than 12 million children, half of them girls, go to school.61

The UK is known internationally for the close collaboration between its diplomats, development officials and military in fragile environments – reflected in the work of its cross-departmental Stabilisation Unit.62 The establishment of the FCDO offers the potential for Britain to integrate even more deeply its diplomatic resources, its work on the linkages between security and development, and its world-leading knowledge of the inner political workings of partner countries with the resources to help them make changes for the better. The UK already spends some 45 per cent of its foreign aid budget on fragile and conflict-affected countries.63 And as one of the world’s main military actors, the UK engages preventively – through deployment of military training missions in countries where it has good diplomatic relations – and reactively to try to uphold security or try to bring peace to conflict situations.