What is Stagflation?

In normal economics, inflation is the price we pay for growth, and higher unemployment is the tradeoff we accept for keeping inflation low. But what if inflation and unemployment are positively correlated? It forms the definition of economic misery.

Stagflation is this economic misery caused by the unholy union of economic stagnation (sluggish growth) and high inflation. The U.S. labor market has slowed sharply, and it is getting clear that inflation is here to stay. Investors are worried that we have already entered into a period of stagnation, with surging prices and a labor market struggling to recover. The debate about Stagflation will intensify over the upcoming months as growth in consumer prices continues to accelerate.

We have been through this before. The reasons behind the Stagflation of the 1970s are complex, but there were three guiding factors:

- A dovish Fed policy in the early ’70s that was willing to take inflation in exchange for reduced unemployment.

- Government spending on new social programs and the Vietnam War.

- Cost-push inflation driven by the oil embargo and rising commodity prices.

It isn’t a lot different today. The Fed is pumping trillions of dollars to stimulate the economy in an attempt to reduce unemployment and promote growth. There has been a massive increase in government spending in response to COVID. Years of underinvestment in commodities and the pandemic-related supply-chain and logistics disruption are resulting in rising commodities prices. We published “Are We Entering A Commodities Supercycle” earlier this month, explaining how popular commodities are set to soar over the coming decade. While some factors are pandemic-driven, the majority are:

- A result of monetary policy.

- The shift in global position on climate change.

- Growing world population.

Effects of Stagflation

Stagflation is a long-lasting economic event that can slowly eat away your portfolio. Warren Buffett mentioned the following in his 1981 shareholder letter:

Inflation acts as a gigantic corporate tapeworm. That tapeworm preemptively consumes its requisite daily diet of investment dollars regardless of the health of the host organism. – Warren Buffett

At this time, it would be hard to find someone who retired in the 1970s. Those under 40 never experienced the dramatic inflation of the ’70s.

- The worst stock performance of the 1970s came not when inflation peaked but when it first spiked rapidly. From 1972 to 1973, inflation doubled to more than 6%. By 1974 it was 12%. In those two years, the S&P 500 declined by a combined 40%. Inflation was higher in 1979 and 1980, topping out at 13.5%; by this time, the S&P 500 had returned to positive performance. Overall, it was a lost decade for stocks and a painful period for retirees.

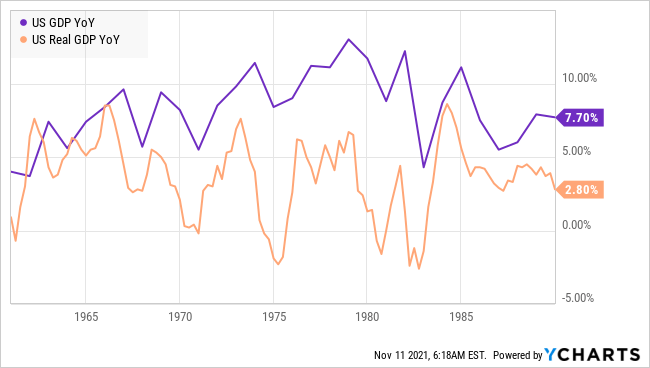

- Even though GDP was growing, “real GDP,” which is adjusted for price changes (inflation or deflation), was underwater. Here is a look at GDP vs. Real GDP from 1960-1990:

Note that in the 1970s, real GDP was negative even as GDP was growing well above 5% annually. This was due to high inflation rates, which exceeded GDP growth.

Stagflation is a serious situation for investors, particularly retirees who rely on drawing from their investment accounts to fund their lifestyle. But are we facing immediate risks of Stagflation now? No.

- There is a surplus of liquidity in the financial system. For corporations looking to borrow, there are plenty of willing lenders. This will continue to fuel growth.

- The consumer is strong. Census Bureau data tells us that retail sales were up 13.9% YoY in September. Americans continue to hold above-average savings and are not hesitating to spend, even though their purchases are more expensive than before.

- The labor market’s struggles are in the worker’s favor. Businesses have plenty of job openings and are looking to hire, practically begging workers to come back into the labor pool. This is very different from the high unemployment rates that are associated with stagflation where businesses are raising prices, but not hiring to expand production.

Stagflation is not happening right now. However, the risk of Stagflation in the future appears inevitable due to critical factors we are seeing. Retirees must maintain a healthy portfolio of fundamentally sound investments that can brace the impact of persistent inflation.

Stagflation is Inevitable

1. Internet is now facing inflation

With the internet came transparency, low barriers to entry into businesses (and increased competition from it), improved outreach, and reduced overhead.

Along with all that came a powerful weapon to combat inflation – price comparisons. To comparison shop in the “good old days”, a shopper had to ride their horse from shop to shop, chipping the various prices into a stone tablet to remember them and let’s not even talk about when you needed to buy a new horse. On the internet, with a few clicks, a shopper can compare prices from hundreds of sellers without getting out of bed. An internet seller has to compete with the best price anywhere in the world.

Hence for several years, the internet was successful in keeping costs low and competitive. In fact, average online prices dropped every year between 2015 and 2019. An important deflationary force for many consumers.

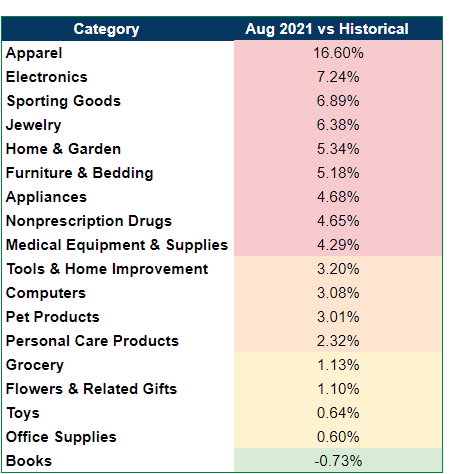

But the pandemic has changed everything. E-commerce is now approaching roughly $1 of every $5 spent by consumers. As online shopping is becoming more ubiquitous, the former cheap convenience is starting to become pricey. Looking at data from Adobe Digital Insights, we see that almost every measured category had higher price increases (or lower discounts) in August 2021 than historical prices in the same period.

– Data Source: Adobe Digital Insights

– Data Source: Adobe Digital Insights

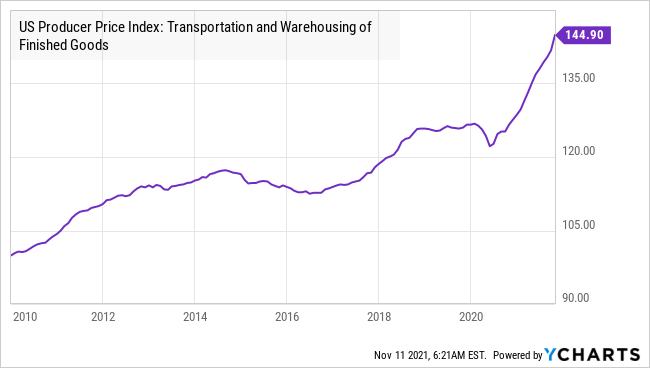

The pandemic has stressed global logistics. Transportation and warehousing costs are skyrocketing up over 12% YoY.

With logistics becoming costlier, retailers are raising prices to customers to preserve margins – we get inflation but not necessarily growth. So the former weapon to fight inflation has weakened significantly and is no longer doing the job.

2. The Great Resignation

Historically, during economic calamities, people aggressively look for jobs. There will be more unemployed people than job openings. Employers have the leverage to determine pay, benefits, etc., and have their pick of candidates from the labor pool.

But this pandemic has proven to be no ordinary economic calamity. A large number of American workers are leaving their jobs. In August 2021, around 892,000 workers quit accommodation and food services jobs, 721,000 quit retail positions, and over 500,000 workers quit healthcare and social assistance positions (Data Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics). The U.S. is facing a massive shortage of healthcare workers. State health officials and medical workers have spent the past 18 months in the trenches. The resultant burnout has left many hospitals short on essential staff.

We now have more job openings than unemployed Americans, and employers are offering higher wages and one-time bonuses to sweeten the deal. Workers have more leverage than ever before.

There have been 20% higher resignations in August 2021, with 4.3 million people resigning compared to the same month in 2019. This phenomenon is called “The Great Resignation.” No more worker surplus means employers don’t get the luxury of picking from multiple candidates.

Household income levels are higher, and many two-income households have become one-income households. This is either because they can afford to do so or because childcare costs are so high that one parent chose to take up the responsibility. Since the start of the pandemic in 2020, three million women have exited the job market, and the number continues to show signs of bleeding. (source: CNBC)

According to a survey by Adobe, Millennials, and Gen-Z are among the least satisfied at work. The pandemic burn-out aggravates the sentiment, and this age group wants their workplace experience to mirror the seamless, flexible experiences in their personal lives.

Thanks to Fed’s monetary policy, 401(k) retirement accounts have grown considerably, enabling older workforce members to pursue early retirement. Roughly two million more people than expected have joined the ranks of the retired during the pandemic, according to The New School’s Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis.

So our workforce is shrinking as we are losing our youngest and the oldest members. The reasons for leaving the workforce are numerous, but the net impact is the same. Millions of people haven’t returned to work, and there is good reason to believe that they won’t return to work. The effects of these will be long-lasting and devastating for some businesses.

3. Dovish Fed

In the 1970s, the Federal Reserve policies were geared to contain inflation and were seen as broadly hawkish.

– Source: dailyfx.com

At this time, we face rising energy costs, and with inflation above 5%, the real returns produced by many investments are negative. The Federal Reserve has two options. They can either take a hawkish stance and attempt to control the rising prices or choose to be dovish and try to reduce unemployment and improve output by maintaining a low cost of borrowing.

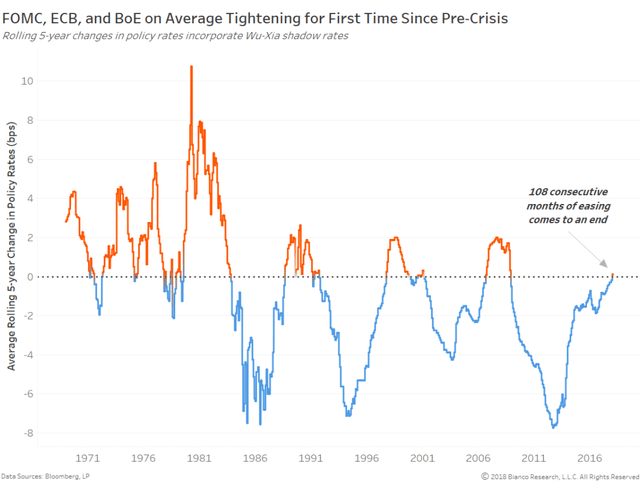

The chart below explains past monetary policy trends. In the late 70s, after we hit stagflation under the Nixon/Ford government, the Carter administration (under Fed Chair Volcker) had to reverse policy and hike interest rates significantly which hit the United States into a big recession in the early 80s.

But over time, we see that the Fed can stay hawkish only for a short span before being forced into a dovish stance. This chart ends in 2017, but we know that quantitative easing began again in early 2020 to protect the economy from the perils of the pandemic.

– Source: theotrade.com

– Source: theotrade.com

It is not a secret; this Fed has explicitly stated it is willing to let inflation “run hot” to reduce unemployment. The problem is that accommodative policy is only capable of encouraging companies to create jobs by ensuring they have ample liquidity. It does not and cannot force people who don’t want to work to take those jobs. Yet the Fed continues to focus on the number of jobs as if they have the power to do anything about it.

This makes the Fed’s stance far more dovish than in the 1970s and ’80s. History tells us that every time inflation has run hot, and the Fed fails to nip it in the bud, it goes from “running hot” to “running wild.” The Fed is not going to act preemptively, it is not concerned about inflation, and it will allow inflation to run.

So we can have better output with higher inflation, right? Wrong – as we saw in the previous section, a large number of Americans voluntarily withdrew from the workforce and showed no signs of coming back – despite higher wages, increased flexibility, and other benefits. Without an entire workforce, the output can only grow so much before plateauing (hitting stagnation). The way it looks now, the Fed’s persistent dovishness makes Stagflation inevitable in the future.

4. Excessive Money Supply

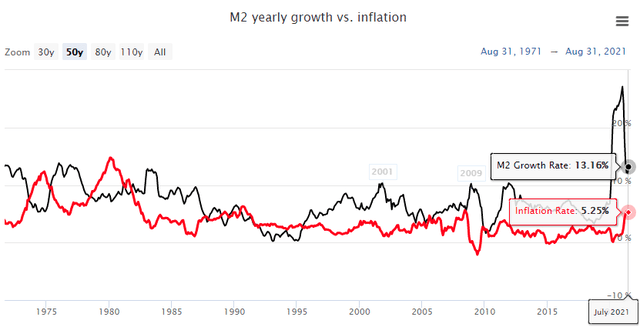

We talked about high retail spending, indicating that we may not be at immediate risk of Stagflation. But it has the potential to fuel inflation. There is a reason for great numbers from retail sales. Large-scale fiscal loosening in the U.S. has caused the private sector to amass significant savings (referred to as M2 money supply – cash, deposits, and savings), which are being unleashed in the economy through government stimulus and have grown as virus restrictions have been removed and confidence returns. In fact, the amount saved is more than anything we have seen in recent times and is comparable to the mid-’70s.

– Source: longtermtrends.net

– Source: longtermtrends.net

In the early ’70s, the M2 money supply remained higher than inflation, but the trend quickly reversed as Stagflation progressed. There is a risk that a rapid rundown of lockdown savings will further fuel inflation and worsen the shortages of intermediate goods.

– Source: Shutterstock

5. The Highest Risk for Stagflation: Ever Rising Wages

In addition to “The Great Resignation” of people leaving their jobs (point #2 above), there are many factors at play that will result in wage inflation for years to come.

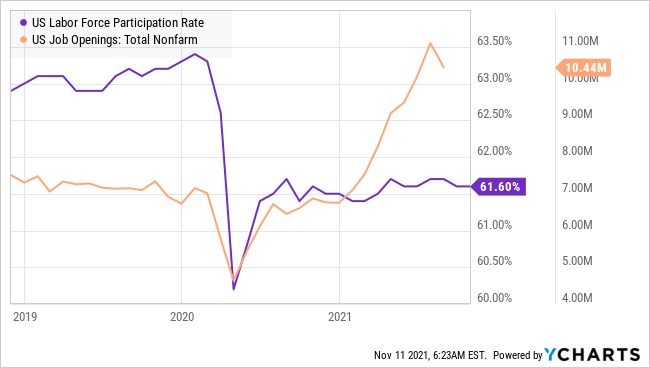

Today, virtually every business that employs workers is unable to fill positions. The U.S. labor-force participation rate stuck at 61.6%, below the pre-recession level of 63.3% in February 2020. Staffing shortages are hitting almost every industry, including restaurants, hotels, resorts, food services, wholesale trade, education, healthcare, and state and local governments.

On a daily basis we are bombarded with news about supply chain and logistics disruption due to the global pandemic. Did you know that shortage of workforce was one of the underlying factors?

Imported products are overwhelming U.S. ports, waiting to be unloaded because there aren’t enough longshoremen and truck drivers. The shortage of truck drivers isn’t new. The problem that existed pre-pandemic has only worsened since.

The shortage of microchips has limited the production of automobiles, home appliances, and many other products. Manufacturers have to shut down work shifts and limit production due to worker shortages and supply-chain disruption. These have resulted in consumer and producer price index hitting record-high levels not seen in decades.

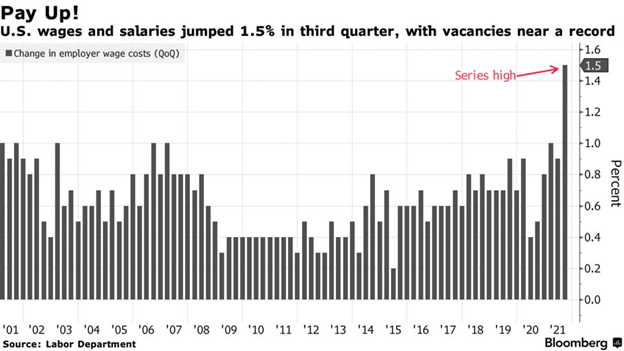

To our point, these pressures have also resulted in the Q3 employment cost index leaping by 1.5%, the largest quarterly increase since 2001, as companies across a swath of sectors resorted to higher pay against a backdrop of labor shortages.

This is alarmingly big.

Rising labor wages will not be transitory, but prolonged due to structural problems formed over decades.

- Discrediting and discouraging blue-collar work: In the past decades, society has convinced everyone that kids who lacked the desire or aptitude to go to college were destined to be second-class citizens. Work and a good life would not be available to them unless they have college degrees. Who would work in factories, on the fields, or do physical and manual labor if everyone pursued white-collar jobs?

- Low birth rates: The American birth rate fell for the sixth consecutive year in 2020, with the lowest number of babies born since 1979. The rate dropped for moms of every major race and ethnicity. According to the CDC, this rate has generally been “below replacement” since 1971 and has consistently been below replacement since 2007. Today, the U.S. total fertility rate sits at 1.6 – another record low.

- The retirement of baby boomers: The baby boomers generation born between 1946 and 1964 represent 21% of the U.S. population. The phased retirement of baby boomers over the next few years creates a massive void in the workforce.

- A broken immigration system where many immigrants either do not have the skills required, face cultural, integration problems, in addition to anti-immigrant rhetoric.

- A growing welfare state encourages people not to work.

Today, there are 10 million unfilled jobs, with 51% of small businesses unable to find staff to hire or expand their businesses. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics is projecting an annual “GDP growth” of 2.3% from 2020 to 2030, which is close to the Congressional Budget Office projection of 2.4% average growth. This is highly ambitious compared to the prior two decades when GDP grew 1.7% annually. Note that there are two components to GDP growth, which assume:

- Productivity gains: Labor productivity increasing 1.7% annually from 2020 to 2030, which is a bit unrealistic given that it only grew 1.1% during the past decade.

- Increase in Labor supply: Total employment is projected to grow by 7.7%, from 153.5 million to 165.4 million over the 2020–30 decade, an increase of 11.9 million jobs. This would require an increase of roughly 1.2 million workers annually!

How will we increase the labor force by 1.2 million per year if we cannot fill 10 million jobs today? It gets worse. By 2030, all baby boomers (who represent 21% of the population) will be at least 65 years old. This large portion of the population is set to retire soon, and it is clear that employers will need a strong workforce plan for replacing retiring workers. The number of Generation X workers is insufficient, while many Millennials lack the necessary work experience or are simply unwilling to join the daily-grind.

The upward pressure on wages and employment costs will continue to result in higher prices for consumers and contribute to the risk of stagflation.

With overly ambitious productivity gains and unachievable labor force gains assumptions, there is a real risk that the economy could stagnate. At the same time, inflation growth has been under-estimated by the Fed and, in my view, will run much higher than the new Fed projections. This could very well result in negative GDP growth (calculated using nominal GDP minus inflation), which is the perfect storm for stagflation.

I am describing the critical ingredients for a new round of stagflation, similar to what we saw in 1970. The prospect of prolonged higher inflation is alarming, driven by a long-term shortage of workers throughout the economy.

What Should Investors Do?

We have demonstrated that Stagflation is portfolio destructive. Critical factors surrounding our economy tell us that Stagflation may not be far away. It is essential to act preemptively and make investments in healthy companies capable of producing returns above inflation.

In his 1981 shareholder letter, Mr. Buffett continued his inflation tapeworm analogy by saying:

Whatever the level of reported profits (even if nil), more dollars for receivables, inventory, and fixed assets are continuously required by the business to merely match the unit volume of the previous year. The less prosperous the enterprise, the greater the proportion of available sustenance claimed by the tapeworm.” – Warren Buffett

This means growth companies that rely on tomorrow’s money will experience valuation contraction. At the end of the tunnel, many of today’s less profitable and unprofitable companies and the investments made in them may not exist.

Warren Buffett began investing at the age of 11 during World War 2. He has publicly said that he doesn’t let macroeconomic events come in the way of buying fundamentally strong businesses at cheap prices. But that is the hint – he buys prosperous companies with massive cash flows that can afford to maintain the business while inflation ravages the economy.

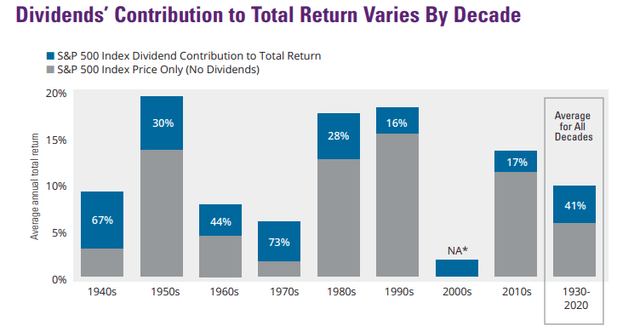

The good news is that most of the stocks you can buy to protect your income stream are similar to the ones we have been recommending to our members all along. Dividend stocks are like the Mazdas (OTCPK:MZDAY) of the investing world – they may not stand out on the streets, but they are highly reliable. During the troubled times of the 1940s, 1960s, and 1970s, dividends played a significant role in the market’s total returns.

– Source: Hartfordfunds.com

– Source: Hartfordfunds.com

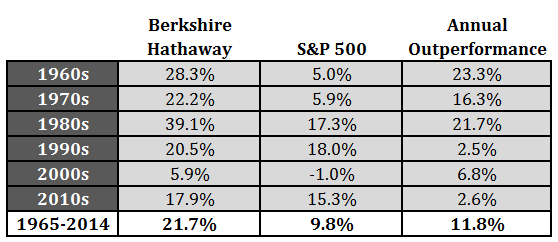

During the ’70s and the ’80s, as inflation destroyed the returns of both stocks and bonds, Berkshire Hathaway’s (BRK.A) (BRK.B) portfolio still compounded the company’s stock with double-digit real returns.

– Source: awealthofcommonsense.com